BCC congratulates the 2021 winners of the 10th Annual Herbert Randolph Kiser Memorial Scholarship, Branden Garcia, Grace Wagner, and Abigail Gauch.

The Herbert Randolph Kiser Memorial Scholarship was established to help young people realize their full potential. Herbert Randolph "Randy" Kiser was born in Waltham, Massachusetts in 1956. Randy received the majority of his formal education in the Boston Public Schools and last attended Boston English. In May 1974, Randy was returning home from work when he was approached by two young men on Gallivan Boulevard near Neponset Circle in Dorchester. Randy’s life was taken as a result of a racially motivated attack.

The scholarship was established for the singular purpose of helping a young person realize their full potential since Randy is unable to realize his. Recipient(s) are graduating Boston Children's Chorus seniors who are bound for college, who are civically engaged, and who have demonstrated a commitment to diversity and the well-being of humanity.

This year, three Herbert Randolph Kiser Memorial Scholarships were given:

- Branden Garcia received $10,000

- Grace Wagner received $5,000

- Abigail Gauch received $1,000

Branden Garcia

Prompt: This year, how have you contributed to equity, demonstrated empathy, and a commitment to justice in your community?

The Columbus Statue Lies in The City Council Chambers

I am not a threat, nor am I a victim. While my ancestral lineages that lie behind may have been victims to the direct colonialism that laid its wrath upon the Caribbean Isle, it is something I only simply inherit. Pledging to dismantle White Supremacy in all forms, whether social or governmental, I promise to enact progressive change in my community.

Operating as the current Chelsea Youth Commission (CYC) Secretary, part of a city board composed of all youth, I represent the voice of Chelsea. I am the brown curly hair you see bouncing around with every step, the enthusiastic sound of laughter and broken Spanish, and I am like any other youth that resides in my city of Chelsea. Therefore, I should be no different from anybody; but sadly, children of color are treated differently, receiving wrath, hate, and unfortunately racism.

It comes in a range of forms, from the glares walking down the streets to the women who run back to their cars clutching onto their purse in aggressive fear. Yet, one of the most common forms of oppression that resides on my shoulders seems to be the looming figure of Christopher Columbus that stands in Chelsea Square. Most widely known as the “Founder of the New World,” Columbus never was and never will be anything more to me than a cruel colonizer who made it his mission to conquer the lands of the many Indigenous peoples within the Americas. To some in Chelsea, these Indigenous peoples of the Americas were our ancestors—massacred physically and culturally. The statue is a representation of nothing other than White Supremacy, an issue that plagues every POC community in Chelsea and beyond.

Chelsea residents should not have to view a symbol of colonization in their city, much less in their neighborhood. No child, parent, or person of color deserves to see a symbol of White Supremacy, a symbol of genocide, and a symbol of their scarred ancestry in such a city as Chelsea that claims to care for and love all. I feel the pain that rumbles through Chelsea residents as they live with this statue. I crave to amplify the voices of the Chelsea youth and families who yearn to remove it. I knew I needed to take action.

As a member of the CYC, it is stated that my main job is to “advise and assist the City Council, the School Committee, and the City Manager” in the plethora of plans and agendas they go through, as stated in the Commission’s mission statement. I am the youth voice that speaks up, defending families and fighting for the best interests of every person in Chelsea, as many families cannot due to their documentation status or for other reasons. However, the Columbus statue cemented down to the crude concrete cube it resides on is supported by more than just gray slop. The framework of the U.S. continuously ensures White supremacy is kept in place by politicians.

At the city council meeting that would determine the removal of this statue, I had taken it. upon myself to speak up during the public comment portion of the meeting on the behalf of the community, eager to advocate for change; however, I was accused of not knowing my history regarding Christopher Columbus. I was viewed as a threat to those who wish to uphold the influence of colonizers. Spiteful comments I received included: “if we’re going to take down the Columbus statue, we might as well get rid of your Hispanic last names.” These words exemplified anti-Latino and anti-Indigenous claims that speak against the majority of Chelsea’s residents. Colonization has plagued the histories of our original cultures, only to be stamped with a Spaniard last name, a mark we wear signifying that we have been branded with the effects of this terror.

Knowing the scars that seemed to bleed once again that night, I could not stand for this injustice which continued within the city I called home. Although the vote to remove the statue was passed 6 to 2, I quickly began organizing. Gathering youth and residents from all over the Chelsea and Boston area, educating them of the deplorable racism exhibited at the city council meeting. Many in our community were motivated to condemn the councilors—their words having so much weight as their beliefs, biases, and discrimination leaks into our local city politics, affecting all. One Columbus statue was brought down, but I was now left to tear down another: one that possessed itself under the cold marble ceilings of the city council chambers.

Our words were our rope, tied to all sides of this metaphorical statue, speaking out and condemning the councilors who dared be discriminatory in our city. Rapidly, this resulted in a city-wide conversation regarding racism in the city government and what steps were needed to be inclusive and equitable. The press was aware of this matter and the general public of Chelsea was able to see who rightfully stood for their rights and their liberty, hopefully being reflected in the replacement of said city councilors through this upcoming local election—votes that would tear down the other statue that lay in the city council chambers.

The belief that our city would become a safer environment for every single resident was all that we needed in that moment. Praise was said, but in true Chelsea fashion, it wasn’t needed. We were there for each other, and that’s all that mattered. Our presence and drive will forever echo in the Chelsea City Council chambers for as long as it stands—a reminder that something that can be built up can be just as easily torn down. In the end, it would be untrue to say that I wasn’t happy to have taken the chance to speak up against the veneration of historical figures who do not represent the true ideal of what the U.S. should and can be.

Grace Wagner

Prompt: This year, how have you contributed to equity, demonstrated empathy, and a commitment to justice in your community?

Go Red and Black

“Go, Sachems!” These words, hurled from a car window as I walked down the street, echoed in my ears, stopping me in my tracks. Three months earlier, I would have assumed that a classmate was excited about returning to school. Last August, however, I knew the words meant something different—they were taunting me for who I am and a way in which I had advocated for justice in my community.

I grew up knowing that I am a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, Aquinnah and I never questioned this fact. However, what I learned about Native Americans in school was disconnected from what I knew about my ancestry. For example, in kindergarten, I made feathered headbands, but I had never done this at home. For a long time, I was not sure what to make of these differences, but when I joined Boston Children’s Chorus at age eleven, I began to understand. BCC uses music to unite diverse communities to inspire social justice and we spent many hours discussing who we were and how stereotypes can form barriers between communities. I eventually recognized that the lessons I had learned about Native Americans were stereotypes. Understanding this helped me to start to embrace my heritage. By the end of my junior year of high school, I knew that my school’s Indian mascot, the Sachem, had to change.

The Sachem is a fierce-looking, red-skinned warrior that guards the entrance to Winchester High School and it has distressed me to the point of tears. A few months before I started high school, I had begun to learn about the rich Wampanoag culture, including the creation stories about the hero Moshup and traditions like powwows and the cranberry festival. When I shared these things with other teenagers, though, many responded negatively. One of my friends said, “The Indians lost the war. You shouldn’t be proud of that.” Even worse, as we learned the trigonometry mnemonic SohCahToa, one boy commented that the word sounded “Indian” and another tilted his head toward me and said, “Just ask Pocahontas over there.” My deep embarrassment was similar to what I felt whenever I looked at the Sachem mascot: I felt unwelcome. Using the skills I had developed having meaningful conversations at BCC, I started talking to my peers about the issue in person and on social media and, although I received negative responses, some even questioning my heritage, I quickly learned not to respond. Instead, I became even more determined to challenge the institutionalized racism in our school. After struggling with this on my own for three years, early this summer, I found people who agreed with me.

Working with the Winchester Student Allies for Native Mascot Change, I immediately threw myself into the fight to retire the Sachem. With the help of the Winchester Network for Social Justice and local tribal members, we worked on educating the community. Despite the negative onslaught from Sachem supporters, we began to make progress. Last July, WSANMC asked me to speak at a School Committee meeting devoted to discussing the Sachem. I accepted immediately. Although the hateful messages started echoing in my mind—“Pocahontas” ringing loudest—I wasn’t going to let that stop me. It wasn’t only about me; it was also about making the school a better place for everyone, including a 12-year-old tribal member at the middle school who would have to go through the same thing. On July 21st, I joined a Zoom call with hundreds of people, and, white-knuckling my wampum necklace, I spoke about my experiences with prejudice and how they conflicted with the school’s mission to create an inclusive environment. A week later, the School Committee voted unanimously to remove the mascot, and before the vote, the Chair cited my testimony.

Today Winchester High School is rebranding and has decided to return to a name it used many years ago: The Red and Black. The community has chosen to honor our town’s history in a way that allows everyone to feel included and, furthermore, accepted. I love my school and now I feel as welcome as everyone else. I can’t wait to return as an alumna to cheer for our teams, proud of both my school and my heritage.

This fall I will be attending Northwestern University to pursue a BA in theatre and a minor in Native American and Indigenous Studies, a program that ran for the first time this year. I hope to continue doing what BCC has taught me to do: combine my love of the arts with my passion for social justice. The stereotypes surrounding the Native American community stem from a lack of education and a belief that indigenous people are only a part of history. I hope to create art as an actor that has the power to shed light on many issues facing the native communities today in an accessible way. Like BCC, I will break down the walls that stereotypes form between communities and help to give people a greater understanding of the world around them and gain a greater understanding of myself.

Abigail Gauch

Prompt: This year, how have you contributed to equity, demonstrated empathy, and a commitment to justice in your community?

My Painful Path to Advocacy

When I was seven years old, my family set off on a long-awaited trip to Disney World. Little did I know, I was embarking on a ten-year roller-coaster ride. By the time I touched down on the tarmac in Florida, a switch in my brain had flipped. I was lost in a sea of anxiety, panic attacks, OCD, loss of memory, inability to read, facial tics, itchiness, and sensory issues. I was subsequently diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety and Non-Verbal Learning disorder. Those diagnoses were wrong.

For ten years, I barely had any relief from my mental health symptoms. Midway through my freshman year in high school, my mother learned about Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS). This autoimmune illness is caused when an underlying viral/infectious trigger attacks the body, causing a wide range of symptoms that are similar to what I experienced. I was officially diagnosed, started treatment, and found a part of myself that I had been missing for ten years.

PANS, in extreme cases, can need more than the standard treatment of antibiotics or anti-inflammatories. Sometimes a patient may need steroids or, in extreme cases, IVIG (an antibody transfusion). This illness is not well understood in the medical community, and children are often misdiagnosed. I learned IVIG was not covered by insurance for PANS. Often, only families with great financial reserves can afford this life-saving treatment for their children and some may require several doses.

Seeing the inequity in our healthcare system, along with the lack of research and awareness that could help thousands of undiagnosed kids, made me furious. I set off with my family to bring a bill to the Massachusetts State House to provide insurance coverage for all treatments and establish an advisory council that would hopefully bring about research and resources to thousands of families in Massachusetts.

I believe that part of the reason this illness lacks the research, attention, and support it needs is a direct result of mental health stigma and the lack of mental health parity. I had learned mental illness is supposed to be treated equally to medical illnesses, under federal mental health parity legislation. This is not happening for children with PANS/PANDAS. I felt this and stigma was preventing PANS/PANDAS from getting the acknowledgment it needed. The illness presents with primarily mental health symptoms, making it hard for people to share their experiences openly. My experience with the illness highlighted stigma in how isolated my family became for those 10 years. No one brought my parents meals or stopped by to check on us when I was in a psychiatric hospital, as they would for a physical illness. People rarely asked how we were. My mother told me friends shared they did not ask because they assumed it was a “private family issue”. I was determined to normalize talking about mental health. I felt doing this would allow others to share their stories and reach out for help and support.

The journey to get the bill to the State House was intense. In July of 2019, my family and I testified at a hearing. While there I met with the chair of the committee, Senator Welch, and shared my personal story with him. I watched my mother speak at the proceedings as she shared the story of our family, and I met many parents and children who had been affected by this disease. The hearing was incredibly impactful, and it motivated me to keep going.

In October of that same year, I worked with the Massachusetts Coalition for PANS/PANDAS Legislation to set up the first-ever PANS/PANDAS Awareness day. This was the largest in-person awareness day in the history of the statehouse. In the following months, I continued to talk with the legislators, hand out pamphlets and information to offices, and send emails in hopes of passing the bill. I also had the privilege of being interviewed for a three-part newspaper article that was published in a local newspaper. Telling my story would mean talking about my mental health struggles publicly, and, while challenging, I knew that my story could help others and increase awareness.

In October of last year, I was asked by the Coalition to tell my story for 2020 PANS/PANDAS Awareness Day. I was able to share my personal experiences with over 10,000, people that day. I was on a video call with legislators, doctors, and a mother who lost her child to suicide because of this illness. For my activism and my willingness to tell my story openly, I received a state citation, and leaders at New England PANS/PANDAS asked me to be a mentor for other children with the illness.

Finally, following an immense amount of dedication, hard work, and perseverance, our bill was passed and signed into law by Governor Charlie Baker on January 1st, 2021. To say I was surprised is an understatement. The bill took over a year and a half to come to fruition, and Massachusetts had already refused to pass it three times before. I was ecstatic.

The healthcare system in our country is far from equitable. My fight did not reform our entire system, but I was able to make a dent. I believe my willingness to tell my story will help others stand up to the intensity of mental health stigma and seek help and support more openly. Now, treatments in the PANS/PANDAS community are more accessible and, hopefully, more equitable to all families, including my own. I am not sure what I want to do in the future, but I know that I am passionate about bringing awareness not only to PANS/PANDAS but to the abundance of inequities present in our healthcare system. My journey has been anything but easy, but my proudest achievement to date was the bill and the impact I made by using my voice.

Prior Scholarship Recipients

- Jillian Baker

- Allyssa Almeida

- Sabrina Marzouki

- Kevin Chan

- Nafisa Wara

- Jessie Rubin

- Ana Mejia

- Emmaline Dillon

- David Blitzman

- Leo Kotomori

- Alex Lee-Papstavros

- Carrie Shao

- Austin Moore

- Sophia Bereaud

- Hal Cox

- Matthew Auguste

- Elizabeth Rozmanith

- Shantel Teixeira

About Herbert Randolph Kiser

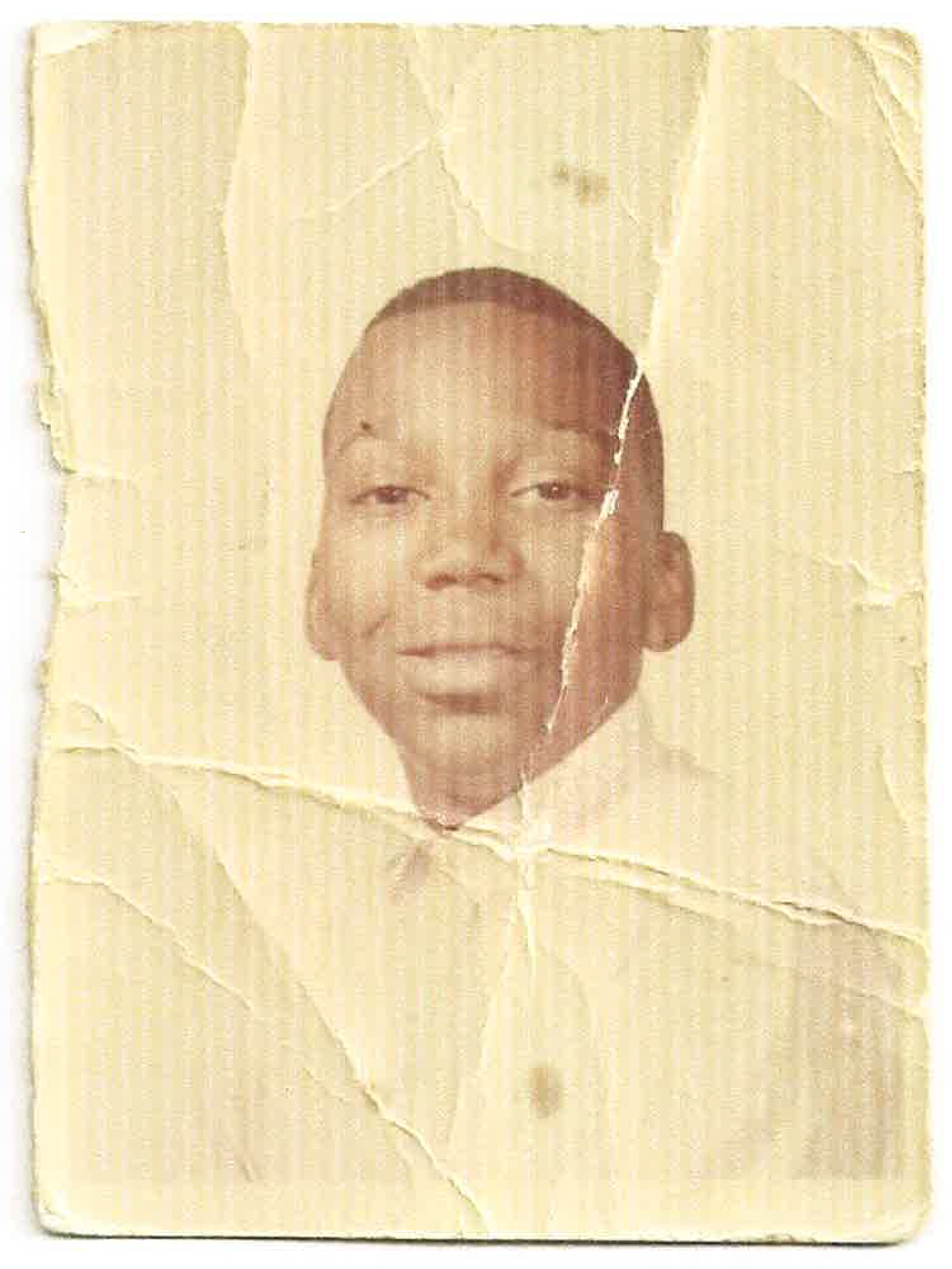

Herbert Randolph Kiser was born in Waltham, Massachusetts in 1956. Herbert, affectionately called Randy by his family and friends, received the majority of his formal education in the Boston Public Schools and last attended Boston English.

On May 15, 1974, Randy was returning home from work when a car occupied by two young men approached him on Gallivan Boulevard in Dorchester. One of the young men exited the vehicle and a brief altercation ensued.

Most, unfortunately, Randy’s life was then taken.

The young man shared that it was solely out of racial hatred that he ended Randy's life. Randy was 18 years old at the time.

The Herbert Randolph Kiser Memorial Scholarship was established for the singular purpose of helping a young person to realize their full potential since Randy was unable to realize his.

The annual scholarship was founded in 2006.

Randy was raised in a family that believes fervently in the value of all people. Believing deeply in the mission of the BCC organization, the scholarship chose BCC as its home in 2012.

Since then, 18 graduating seniors have received scholarships, totaling more than $40,000.

Past Scholarship recipients have attended or are currently attending such colleges and universities as The University of Southern California, Norte Dame, Ithaca College, Elon, Clark, UMASS, Harvard, Boston University, and Berklee College of Music.

Randy's family is committed to social justice, fairness, inclusion, diversity in all of its forms, and supporting all efforts in support of peace and reconciliation in society.